LEBANON’S DILEMMA – A revolving identity crisis

On September 1, 1920 French General Henri Gouraud proclaimed from the porch of the Pine Residence in Beirut the creation and independence of the state of Greater Lebanon under the colonial mandate of the League of Nations represented by France. France also received Syria which it separated from Lebanon, while Britain was awarded Palestine, Transjordan and Iraq.

This series of five articles was originally written in January and February this year by Ghassan Kadi. We are publishing it today on the occasion of the centenary of Lebanon to enlighten readers on the historical role played by French colonialism in the sectarian divide-and-rule strategy of the Levant (Greater Syria) and the internal forces in motion at that time and their role today. France and Britain together separated the region into Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Transjordan and Iraq by secret agreement (Sykes-Picot) during World War I, which they received following the war with the defeat of Ottoman Turkey and Germany as “trustee”. The series also brings out the character of the internal institutions established in Lebanon on September 1, 1920 by the armed forces of France.

This is at a time when the Trudeau government is once again using “aid” to meddle in the internal affairs of another country following the massive explosion of August 4th based on the claim that the “institutional reforms” demanded by Macron of France are the condition for rebuilding Beirut and the country itself. On September 1, François-Philippe Champagne, Minister of Foreign Affairs, issued a statement hailing the 100th anniversary of the founding of the colonial “Grand Liban.” He declared “While this is a significant occasion worth celebrating, it also marks a turning point for the country…. We reiterate that international assistance must be accompanied by reforms and impunity must end.” Not only that, the Trudeau government claims that its intervention is so that “they can have a government that is based on equality, inclusivity and prosperity for all” at a time when the liberal democratic institutions in Canada are mired in deep crisis where emergency powers rule the day. Ghassan Kadi provides information evidencing that a return to being a pro-Western puppet state under the claim of human rights is by no means the sole alternative before the Lebanese people in renewing their national identity. This the Trudeau and other governments do not want discussed. – TS

I. A revolving identity crisis

Abstract for Section 1: There is a deeper side to the current street uprisings in Lebanon than just corruption. It is a matter of defining Lebanese identity, the outcome of which is a Syrian matter. Historically, Lebanon did not start to have a state-like political entity of its own till the 17th Century. Since then, Lebanon had strong ties with the West and emerged as an independent Arab state with Western orientation, unlike other Arab states. But this has all changed and very unexpectedly. It is important to understand this history in order to be able to understand the present and its possible effects on the future as shall be discussed in subsequent articles.

There is a deeper side to the current street uprisings in Lebanon than just corruption. Whilst corruption of Lebanese politicians have left the country virtually bankrupt, the identity of Lebanon is once again under the microscope and the countless number of Lebanese flags that have been flown across Lebanon and by the diaspora Lebanese is a testimony to this.

The outcome of defining the identity of Lebanon however is not far from Syria; both strategically and geopolitically. For this reason, any whichever way the uprising pans out, its repercussions will spill over and one way or another, and will have an effect on the future of the Axis of Resistance.

Fakhreddine’s capital, Deir Al Kamar, in Palmyra located in present-day Syria.

Fakhreddine

Historically, Lebanon did not begin to have a state-like political entity of its own perhaps until Prince Fakhreddine established a state within the Ottoman state. He built a very powerful one hundred thousand strong army, fought and won against the Ottomans and declared autonomy in the early 17th Century. He had substantial connections with the West; especially the kingdom of Tuscany. His reign spread over all of today’s Lebanon and extended outside its current coastal borders, as far as Palmyra (Tadmor) east in today’s Syria. His castle in Palmyra still stands overlooking the ancient city as a testimony of his might.

Non-Arabs are excused when they make statements that allude to lack of knowledge of Lebanon’s national identity, and this is because the Lebanese themselves are yet to agree what their national identity is. As a matter of fact, most of Lebanon’s problems, most of its past and present strife, are all related to this identify confusion and this is the argument that those articles will try to expand on and defend.

To understand the position of Lebanon vis-à-vis Syria we need to go back to the early beginnings. During the Phoenician era in the second and first millennia BC, there was no such thing as a united Lebanon, but instead, there were a few independent coastal city kingdoms. And those city kingdoms were spread all along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean in what is Lebanon today, Syria and of course as far south as Palestine.

The Roman era witnessed strong ties between the Levant (Lebanon included) and Rome. It was once said that the Orontes (a Lebanese/Syrian river) flows into the Tiber. As a matter of fact, four Roman Emperors were of Levantine descent.

During the Byzantine era, the cities flourished, especially Beirut, but it was decimated by a powerful earthquake in 551 AD. By the time of the Muslim conquest, most people were Orthodox Christians, and many converted to Islam. And even though Christians were not persecuted as such, many took refuge in the rugged mountains in order to be left alone and avoid paying tax to the Muslim governments of Damascus and later on Baghdad.

Saint Maroun

Later on Saint Maroun, the Patriarch of the Maronite Church, moved his parish from the Homs district in Syria, where he was born and bred, to Mount Lebanon, again seeking refuge and isolation.

By-and-large, the Muslim population became more concentrated in the coastal cities of Beirut, Tripoli and Saida, whilst Christians occupied the hills. But the hills also were home for the Druze who were persecuted around the 10th Century. This narrative is not about who came first, because both the Maronites and the Druze have been in Lebanon long enough to claim ownership of their homes and identity. The bottom line here is that the central areas of Mount Lebanon of Zawyeh, Kisrwan, Maten, and Shouf which are in today’s Lebanon were home primarily to Maronites and Druze. The northern regions of Danniya and Akkar became eventually predominantly Sunni Muslim, whilst the southern district (Jabal Amel) and the Bekaa areas became Shiite.

French postcard showing four Christian men from Mount Lebanon, late 1800s.

Even though Lebanon continued to have a special status within the Ottoman Empire, its internal sectarian strife was to colour and steer its destiny. By 1843, the divisions between the Maronites and the Druze seemed irreconcilable leading to bloody conflict and massive killing to the point that the Ottomans decided to split Mount Lebanon into separate Maronite and Druze enclaves. But this did not stop the mayhem, and by 1861, after years of killing and pillaging, Western powers were successful in coercing the Ottomans to give Lebanon a political system that reunited the divided people under the auspices and protection of the West. A state was established that was restricted to Mount Lebanon’s Maronite and Druze areas. This version of Lebanon (Small Lebanon) did not include the predominantly Sunni major cities of Beirut, Tripoli and Saida, nor did it include the northern (Sunni) and southern districts (Shiite) of the mountain range.

Of pertinence here is the issue of the emergence of Western influence on and within Lebanon. Beginning with Fakhreddin’s ties with Tuscany in the early 17th Century, European missions began to appear in Lebanon. They established badly needed schools because Ottoman Turkey left the Levantines illiterate, other than what was taught in local religious-based schools.

Of pertinence here is the issue of the emergence of Western influence on and within Lebanon. Beginning with Fakhreddin’s ties with Tuscany in the early 17th Century, European missions began to appear in Lebanon. They established badly needed schools because Ottoman Turkey left the Levantines illiterate, other than what was taught in local religious-based schools.

Before too long, in the mid-19th Century, institutions of higher education were established, the two most prominent of which were the French St. Joseph Jesuit University and the American Syrian Evangelical College. The latter was renamed the American University of Beirut (pictured below).

There were many reasons therefore behind Lebanon’s special status if compared to other post WWII newly-created independent Arab states. The higher percentage of Christians in Lebanon was a huge catalyst for its openness to the West. This is not only because those Christians wanted to look away from Turkey and towards the West, but also because the West itself was interested in establishing a foothold on Ottoman-controlled territory.

Whether the interest in Lebanon on the part of the West was of a religious nature or not, whether the West saw in Lebanon a part of the Holy Land lost to Ottoman Turkey, and whether the West wanted to “use” Lebanese Christians to hit back at Turkey is not the point I am trying to debate here. What is important is the fact that before the current borders of Lebanon were drawn in 1920, and long before the French Mandate was established after the end of WWI, Lebanon already had strong ties with the West; the kind of ties that no other Arab region or state-to-be had.

In stark contrast, the young independent states of Egypt and Syria in particular, had a strong aversion towards the West.

Their political views and aspirations developed a diametrically opposite passion towards the West as that of Lebanon. And as Lebanon was growing closer to the West and reaping the benefits of capitalism and free trade, other Arab states that were once the centre of the Axis of Resistance gravitated towards the Soviet Union and the anti-Western rhetoric.

Lebanon was then seen as a Western vassal state; even some Lebanese shared those views. But after the creation of Israel in 1948, the stature of Lebanon in the eyes of the Arab World changed from that of dislike, to that of putting it at the centre of serious accusations of treason. Former Egyptian President Nasser and his media outlets did not spare a single occasion without making statements to the effect of saying that Lebanon and its government, politicians and institutions is akin to the second worse thing to having another Israel within the Arab World.

The transformation that Lebanon had and which put it at the epicentre of the Axis of Resistance in only a few decades was totally unforeseeable back in the 1950s and 60s. In the coming chapters, we shall see how this metamorphosis happened and how it can affect the region in the near future.

II.

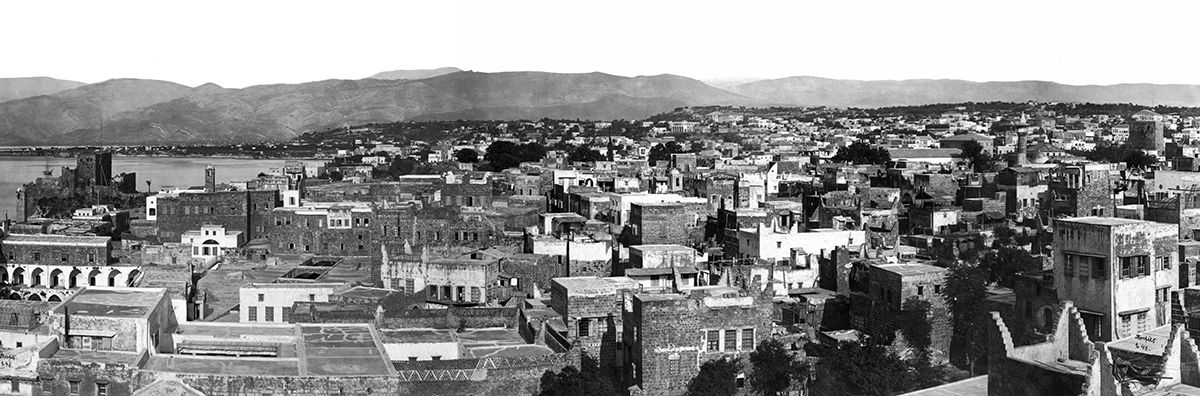

Beirut, late 19th century, by Félix Bonfils.

1960s postcards of Beirut

Abstract for Section 2: Lebanon has seen many recent changes in the last few decades. Formerly a neutral Western-oriented country, Lebanon capitalized on its system of free economy and western style freedom to become the economic and touristic hub of the Levant. The sectarian undertone however was never far away, and that division had people divided over their definition of their identity and loyalties. Some Lebanese consider themselves independently Lebanese, others as Syrians, others as Arabs and some as international. But the current street uprisings seem to be taking traditional rivals into a different direction; one that is endorsing the independent Lebanese identity.

Lebanon played a very insignificant role in all the initial Arab/Israeli wars all the way up to and including the Tishrin/October/Yom Kippour 1973 war, but its destiny was set to change. As a small country that was once neutral enough to earn the title of the Switzerland of the East, it ironically soon morphed to become the centre of resistance and opposition to the NATO-sponsored Israeli roadmap.

Back in the mid to late 1950s, Nasser’s Egypt was the central Arab state confronting Israel, and after Nasser’s triumph in the 1956 Suez war, it was unthinkable that only a quarter of a century later, Egypt would sign a peace agreement with Israel and that the neutral, small, Westerly-oriented Lebanon would turn into the spearhead keeping Israel at bay.

With this new pivotal role, the current civil uprising in Lebanon is therefore potentially a regional turning point; and not one affecting Lebanon only.

So why did Lebanon rise and fall so dramatically and so quickly?

And apart from the prevalent corruption that is behind today’s uprising, what is the underlying cause of unrest? This is what I shall try to explain very succinctly.

Back in the 1940s and 1950s, Lebanon was the only Arab state that had free economy and openness to the West. As the oil money started to pour into Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states, the Arabian Peninsula was very underdeveloped and Lebanon became the obvious route for transit of goods back and forth from the West to the developing Gulf. Even if a Saudi Sheikh wanted to import Italian furniture to fill his palace with, it was shipped to Beirut and then carried on Lebanese trucks to Saudi Arabia. But this is not all, a fair chunk of Iraqi oil used to be piped to the Lebanese coastal city of Tripoli (not to be confused to Libya’s Tripoli) and carried by tankers from there onwards to Europe and other destinations.

That same period also witnessed a huge exodus of tertiary-educated Lebanese technocrats and professionals who went to Saudi Arabia and the Gulf as doctors, engineers, technicians and business people, sending back into Lebanon millions of dollars annually. Last but not least, with its open free economy, open banking system, gorgeous climate, bars, cabarets, brothels and a spectacularly located casino, Lebanon became the favourite tourism hub for rich Arab tourists who lived under strict Islamic rule that banned all of the above.

During this period, Lebanon was abuzz with action; all the way from musical carnivals to opera performances, rock concerts, you name it. During the filming of the movie Lawrence of Arabia in Jordan back in 1961, actor Peter O’Toole used to fly to Beirut every weekend, and when asked why do it so often knowing that he could only stop there for a short while, he said “because it’s worth it.”

In how many countries in the world could one do water skiing and snow skiing in the same day at venues that are only an hour drive away from each other? The gorgeous and versatile nature of Lebanon plus its rich history did not only attract Arab tourists, but Western tourists as well. And whilst one had to run and hide in fear of getting arrested in other Arab states if he stumbled on an American Dollar, exchange shops filled the streets of Lebanon’s cities and touristic venues. One could almost buy a falafel roll with Travellers Cheques.

To add to all of the above, Beirut in particular had a huge number of hotels all the way down from six stars resorts to ones that suit every budget. Restaurants and food shops were plentiful offering same range of pricing as hotels did. One could buy Scotch Whiskey and American cigarettes at a much cheaper cost than in Scotland and America. And though gambling was only legal at the Casino, the police turned a blind eye to illegal gambling venues that were scattered everywhere.

And as if the above was not enough, Lebanon was a tax haven and investors found in it a good business base to invest and “hide” money. Syrian businessmen in particular moved huge sums of money and gold into Lebanon after Syria became socialist. This was how Lebanon earned the name of Switzerland of the East, but over and above what land-locked Switzerland has to offer, despite its snow peaked mountains, Lebanon’s winter is never too cold and it has a 200 Km coastline. Its mild summer did not only attract Arab playboys, but also Arab families. Hilltop towns were constantly inundated by Arab holiday makers who were escaping the scorching desert summer heat back in their homelands.

Moreover, Lebanon was the only Arab state that allowed free journalism, freedom of speech and political freedom. It eventually became the refuge of most Arab political activists who were persecuted in their own countries.

Artist: Walid Zbib, 1990

As the capital of both beauty and vice, during this golden era, the exchange rate of the Lebanese Lira to the USD was two to one, respectively. At this juncture, and just to step forward in time for a moment, the current rate exceeds two thousand to one and slipping.

Lebanon was simply and briefly the envy of the Arab World as well as Israel. After all, Israel could have played a similar role and competed with Lebanon, but the boycotts left it in its box of exclusion and seclusion, and the once very busy port of Haifa lost its transit business to the port of Beirut.

So how did this amazing story of success turn into such a huge failure?

On the surface, we can blame the whole story of failure on sectarianism. Lebanon was never able to bypass this problem that divided its people and destroyed its economy. What we see today on the streets however marks a whole new change and rejection of this status quo, and a deeper look reveals that loyalty could well be taking a new form, and this is because underneath the façade of sectarianism, there is the deeper issue of identity.

Many nations have identity problems, and sometimes there is a sectarian undertone to it as in the Balkans for example. But Spanish people and Catalans are both predominantly Catholics yet identity issues remain unresolved.

But unlike say Croatia where the identity confusion was between two options Croatian or Yugoslav, identity in Lebanon provides three options: Lebanese, Syrian and Arab. This is not to forget the all-inclusive Marxist international one. Indeed, Lebanese youth grew up witnessing a community the members of which identify themselves either as Lebanese, Syrian, Arab or international.

The advocates of Lebanese identity and nationalism were originally predominantly the Lebanese Christians, or Maronites to be specific.

The advocates of Syrian identity are the followers of Antoun Saadeh (a Lebanese) who established the Social Syrian National Party (SSNP) and which advocates the Syrian identity where Syria is the historic Greater Syria and which includes all of today’s Syria plus Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Palestine. Members of this political party are quite secular and belong to all religions and sects.

The advocates of Arab nationalism are predominantly Muslims (with a Christian minority) and they were and are followers of the former Egyptian President Nasser and/or the Baath Party (the founder of which is Christian by the way).

The advocates of international identity are the Communists who at one stage were very numerous and quite strong.

With all of the above said, with or without socio-political ideas like Communism, pan-Arabism and/or Greater-Syria-nism , Lebanon is definitely not a stand-alone nation like say France. Lebanon is historically and geographically the mountainous region of Syria. Its current borders have been drawn by the French General Gouraud in 1920. But since 1920, even the borders of France itself have changed, and so did the borders of many other nations, and this alone does not mean much.

When Lebanese-American historian Phillip Khuri Hitti wrote his book about the history of Lebanon, he did not name it “History of Lebanon”. He named it “Lebanon in History”. After all, with its metamorphosis from ancient Phoenician city kingdoms to being part of empires, revolving borders and restructuring, Lebanon did not have a history that was independent from the history of its region. This in itself brings us back to the present and emphasizes that whichever way the current uprising ends, it will have its repercussion waves spreading all over the region.

Before I end this I must emphasize that personal freedom in Lebanon came with a societal cost. Not only one could walk into an exchange shop and buy US dollars, but a few doors up or down one could buy any amount of world-renowned locally-grown Hashish. The pharmacy next door would sell antibiotics and morphine without a doctor’s script. Another shop would sell Kalashnikovs (AK47), M-16 assault rifles, you name it. The kind of freedom Lebanon “enjoyed” was closer to lawlessness and even anarchy than responsible right of self-determination. When the Lebanese Army barracks of Tripoli were ransacked in 1976, the loot was sold by street vendors and it included items like mortar shells. Who in his right mind would buy a mortar shell and what for? In Lebanon they do and they display it in their living rooms like trophies.

Actually, the black market price of a Kalashnikov is seen as an economic indicator. It is also seen as a security indicator except that it goes up on two opposite trigger factors; demand preceding strife and the occasional government crackdown.

My wife, a Westerner, was flabbergasted as she was in a sewing machine shop when suddenly a man wielding a Kalashnikov walked in. She thought it was a hold up, but apparently the man knew the shop owner and he was asking for a bit of oil to lubricate some parts on his Kalashnikov. Such is Lebanon.

As Lebanon lost its Switzerland of the East title during the civil war and as it made a U-turn from almost total neutrality to becoming the centre of the Axis of Resistance, the twists and turns did not come by easily, and the Lebanese people remain divided as to how to define themselves, what identity to accept and uphold, and what position in the world they belong to. For better or for worse, the “Lebanese” Lebanese identity is currently becoming more demographically acceptable by Lebanese Sunni Muslims who by-and-large repudiated it not long ago. Their values and aspirations are finding congruencies with those of their traditional rivals, ie the Christian Maronites who are also finding commonalities with a much older rival and foe; the Druze.

The cycles of violence and destruction seem to have taken the traditional Lebanese Maronites, Sunnis and Druze to a common denominator, an intriguing fact, given that it was the rivalry and differences between those same groups that destroyed Lebanon back in the civil war and dethroned it from Switzerland of the East title. But the cycle of intrigue is not over yet. It is as if Hezbollah alone was not the only unexpected wildcard, the uprising is adding more unknowns and speculations and another cook to meddle with the brew that already has many more cooks than it can handle.

III. The Birth of “Grand Liban”

French General Gouraud marches through the deserted streets of Aleppo on September 13, 1920. Just as British General Allenby had taken a stroll in the old city of Jerusalem in 1917 and declared, “Today the Crusades have come to an end,” his French counterpart in Syria, upon taking Damascus went straight to the tomb of Salahuddin. Standing at that most green-draped of tombs in the Ummayad mosque and, in what must be one of the most inflammatory statements in modern Middle East history, Gouraud placed his boot on his grave and declared to the tomb: “Saladin, we have returned.” Or: “Look Saladin, we are back!” Another account has him declaring “The Crusades have ended now! Awake Saladin, we have returned! My presence here consecrates the victory of the Cross over the Crescent.”

Abstract for Section III: “Grand Liban” – as the French called it – is Lebanon in its current borders as compared to the much smaller version that was comprised of the Maronite and Druze areas only. The new state was announced on September 1, 1920 and the Maronite Church under Patriarch Howayyek played a big role in the decision making. The move was opposed by the Syrian National Congress. The battle of Maysaloun followed and France entered Damascus forcefully after the glorious defeat of the Syrian Army and the martyrdom of its leader Yusuf Al-Azma. Residents of the Lebanese Coastal cities of Beirut, Tripoli and Saida (predominantly Sunnis) refused the new entity and regarded it as a Western vassal.

The brazen role of the Turkish Army in the current situation in Idlib serves as a good reason to remember that ever since the battle of Marj Dabiq in August 1516 and which eventuated in the fall of all of Syria to Ottoman troops, Turkish military presence did not completely leave Syrian soil and historically Syrian cities such as Adana and Antioch are technically still under Turkish occupation.

The battle for Syrian sovereignty has therefore been going on for centuries, and it certainly did not end. It is much more ancient than the loss of Golan and even the creation of Israel. Syrian territory has been chipped away and taken violently by invaders at times when Syria was weak and unable to defend herself.

But whilst the Israeli occupation of the Golan, and to a lesser extent the Turkish occupation of the Iskenderun and Cilicia provinces, are easy to identify as being foreign, the chipping away of Lebanon is more subtle, because Lebanon is meant to be an independent Arab state that enjoys good relationships with Syria. In reality however, Lebanon has historically been a part of Syria, and when the French drew its current map, the move was opposed by the Syrian Government as well as by a majority of civilians on both sides of the borders.

On the 1st of September 1920, French General Gouraud announced the birth of Grand Liban (Grand/Great Lebanon) in its current borders. Back then, it was questionable as to whether or not this new state was to see its first centenary. As we approach this landmark, the question remains viable even though we are only less than a year away.

When Gouraud drew the map, one of his objectives possibly was to establish a state in which there was no overwhelming majority. He might have thought that instead of having a state that is comprised of Maronites and Druze only, by adding Sunni and Shiite elements to the demographics, the population would be so diverse that no single party would be strong enough to cause strife.

It can also be argued that a bigger and a stronger Lebanon would be stable and a better French ally in the future.

Others will argue that his objective was to divide and conquer Syria and that the exact location of the Lebanese borders did not mean anything to him. There is no doubt that this theory holds a lot of ground, especially that the creation of the independent state of Lebanon was in itself an attempt to fragment and weaken Syria. The issue at hand here however is the placement of the border line he chose. It is about trying to answer the question of why did he include the Sunni and Shiite regions? Why did he not leave them both or at least one of them with Syria? What made him choose those particular borders for Grand Liban?

Whilst it is true that the Sykes/Picot accord divided the Levant (Greater Syria) between British and French-controlled territories, it would be right to say that it was by French, not British, action that Lebanon was split away from Syria and given independence. With all of the above said, the Maronite Church played a huge part in the creation of Lebanon, if not the biggest part, and the French only needed to be convinced, and as they did they complied and delivered.

To put it bluntly, as the Ottoman Empire collapsed, the Maronite Church wanted to secure that Lebanese Christians will not ever fall under Muslim rule again. The head of the Church back then was Patriarch Elias Butros Al-Howayyik. He was a strong and outspoken opponent of Turkey and was in fact persecuted by the Ottomans and put under home arrest. He was only released after the Vatican and France intervened.

A clear distinction however must be drawn between patriotic Levantine Christians and the position of the Maronie Church at that time. Certainly, Christians in general and Maronites in particular did not unanimously agreed with the vision of Howayyek and it would be unfair to even try to speculate what percentage did. As a matter of fact, many leaders of the political Lebanese and Syrian Left have been Christians. Patriotic Lebanese, Syrian, Palestinian and other Arab Christians remain till today as an integral part of the heart and soul of the Axis of Resistance. And back a century ago, during the period known as the cultural awakening, most Syrian and Lebanese patriotic writers, poets and journalists of influence were Christians.

Leading up to WWI and after long sectarian strife, the state of Small Lebanon (Mount Lebanon without the coastal cities) was created and put under Western protection as we have seen in previous articles. As the war broke out and Turkey and the West were on opposite sides of the fence, Turkey abolished the special status under which Mount Lebanon was, put the area under siege and prevented any food supplies from entering. Purportedly, one third of the civilians died from starvation. It was an act of Ottoman revenge because the Ottomans did not like the Western intervention into the affairs of its territories and putting Mount Lebanon under special privileges.

If anything, the harsh treatment and starvation made the Maronite Church more determined to seek total independence from anything that was reminiscent to the past; and this included Syria because Syria has an overwhelming Muslim majority. In brief, they wanted Lebanon to become a Christian-controlled state with a Western outlook and very little to do with its own region.

So why was it exactly that Patriarch Al-Howayyik insisted that the big coastal cities of Beirut, Tripoli and Saida be added to the new state knowing that they have a Sunni majority? No one really knows other than speculating that in forming a new state that has a powerful Maronite Church and political entity, one that guaranteed that the head of state (ie President) and Army Chief are both Maronites, will be able to survive and bring protection and security to the Christian population. Perhaps he also thought that a larger Lebanon with major cities and ports will be more economically viable.

In the 1920s Syrians display cultural and religious diversity and harmony.

Syrian National Congress held in Damascus, Syria in May 1919.

As the Patriarch was doing his bid trying to convince the French that Lebanon needs to be independent and modelled on his own vision, quite at the opposite pole the “Syrian National Congress” was convened in Damascus, Syria in May 1919. In its final report, the Congress concluded that “there be no separation of the southern part of Syria, known as Palestine, nor of the littoral western zone, which includes Lebanon, from the Syrian country.” The Congress declared independence and appointed King Faisal as head of state. Reading in between the lines it is clear to see that an independent Lebanon was perceived to be almost as unacceptable as the creation of Israel.

The Independence did not last long. France and Britain had secretly agreed to divide the Middle East into French and British ‘spheres of influence’. In 1920, French troops landed on the Syrian coast, threatening to occupy the country. The Syrians decided to resist. At the town of Maysaloon, on the outskirts of Damascus, the ill-equipped Syrian army was defeated, and Defence Minister Gouraud was killed in the battle, which marked the beginning of 26 Years of French mandate over Syria.

Yusuf Al-Azma

The French response was brutally swift, and it was meant to crush what they saw as a rebellion. A modern French army of 12,000 men equipped with tanks and supported by warplanes was sent to enter Damascus and forcefully if needed. But the former capital of the Omayyad Empire was not going to greet the invaders with roses. Army Chief/Minister of Defence Yusuf Al-Azma was sent with very ill-equipped few hundred soldiers and few volunteers to make a mark in history. They knew they had no chance of winning, but they wanted to die standing. The heroic defeat in which Al-Azma himself was killed remains as one of Syria’s greatest stories of glory.

Syrians will never forget Maysaloun.

It was only a few months later, in December that French General Gouraud announced the birth of “Grand Liban”. In his speech, he referred to Maysaloun as a battle that the French have fought to save Lebanon, and perhaps in retrospect it was; but not from foreign invaders as he put it.

With the declaration of “Grand Liban” as a separate entity, two opposite passions developed across the borders between Lebanon and Syria, and those passions deepened over the decades. In Syria, a growing concern that Syrian territory has been chipped away bit by bit.

First of all, Turkey kept the district of Cilicia, then Lebanon was created, then the French gave away the district of Iskenderun to Turkey as a sweetener, and last but not least, Palestine was chipped away and Israel was established. It is little wonder why patriotic Syrians galvanized behind President Assad to thwart the greatest of all attacks back in March 2011, but this is another story.

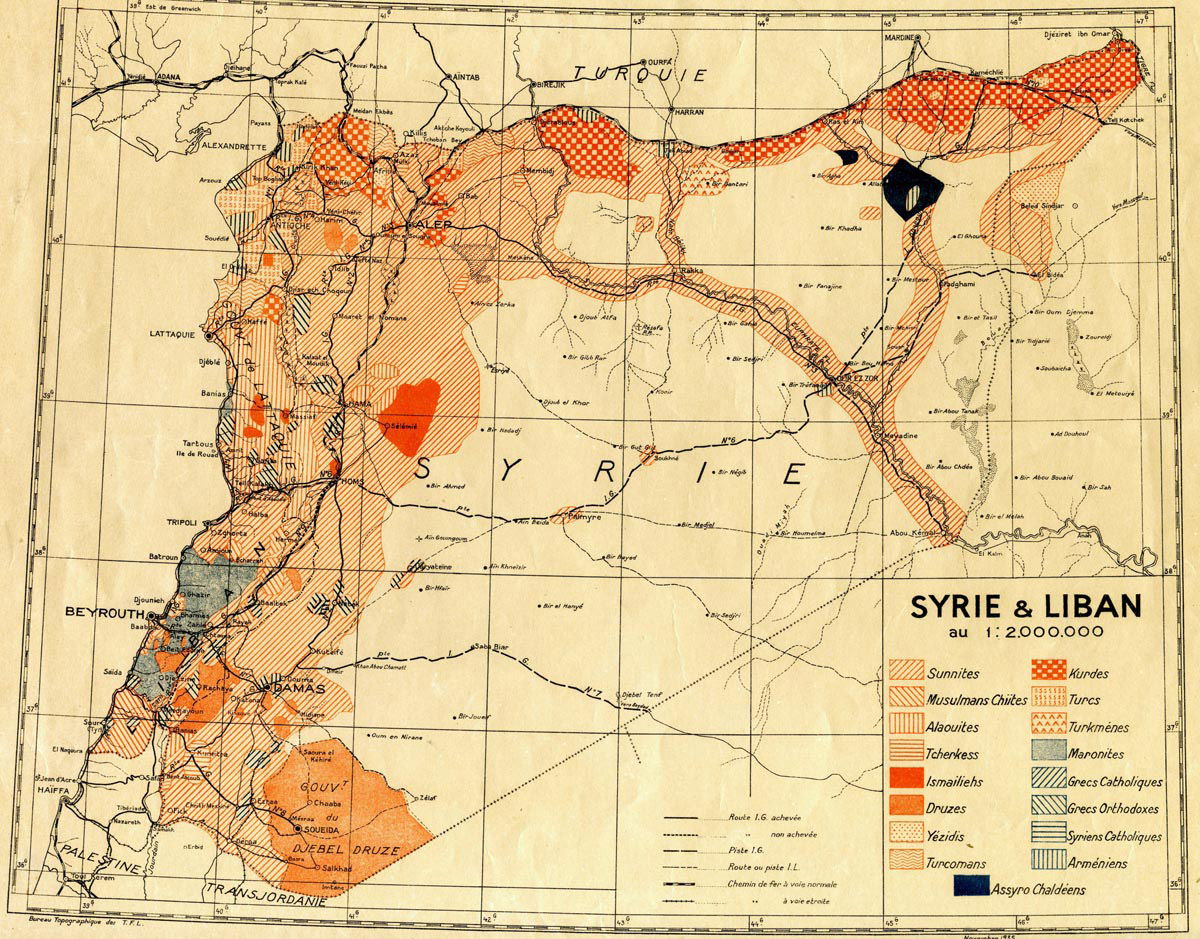

Population map of Syria and Lebanon, c.1935.

Lebanon was seen in Syria as a Western vassal, a love-child of the West and a byproduct of sectarianism; and in more ways than one, it was.

On the other side of the coin, when Lebanon eventually became independent, to the Maronite Church and political establishment, independence was mostly seen and celebrated as independence from Syria; though Syria historically was neither a culprit nor foreign.

Patriarch Al-Howayyik finally got what he wanted and Lebanon became a stand-alone state in its current borders.

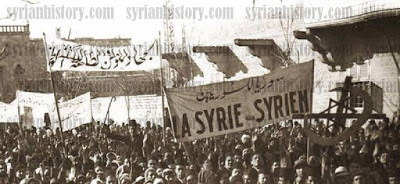

The declaration of “Grand Liban” had a mixed response. Those who wanted an independent Lebanon, who were mostly Christian Maronites were celebrating. However, city dwellers who were mostly Sunnis were revolting.

Not only did the people of Beirut, Tripoli and Saida, in all of their religions and sects, refuse to be sliced away from Syria, but they also did not want to belong to a state that will forever be a Western puppet; or at least this was how Lebanon was seen in their eyes. They took to the streets demanding Syrian unity, secularism, and upholding the resolutions reached by the Syrian National Congress, but to no avail. The decision was already made and the battle of Maysaloun was already lost.

Many if not most of the Sunni Lebanese partaking in the current street uprisings brandishing Lebanese flags have no idea at all that a hundred years ago their great grandparents took to the streets denouncing the precursor of this same flag. This part of history is not taught in schools in Lebanon, but in Syria, every man woman and child knows that Lebanon was taken away from Syria by the treachery of the West and complicit action of certain Lebanese groups.

Back in the 1920s, the Syrian identity of Lebanon was not questionable and if anything, it was the Lebanese identity and nationhood that was repudiated and even ridiculed by most. Among other legacies that still live on, it is very obvious in the writings of Gibran Kahlil Gibran, a Maronite who considered Lebanon as a part of Syria.

Much has changed over the last century, and the Lebanese did not stop to wonder and ponder what their real identity is.

Does the current uprising reveal any change? This is what we shall try to examine in the upcoming articles.

IV. The emergence of the role of Lebanese Shia

Abstract for Section 4: The 1943 Lebanese constitution was reached by consensus mainly between the political Maronite and Sunni leaders; all in accordance with the initial plans of Patriarch Howayyek. The constitution stipulated that the main positions of power were given to the Maronites, these are namely the position of the President and Army Chief. The Sunnis got the position of the Prime Minister, the Druze had the army’s Chief of Staff and the Shia got the token position of the Leader of the House. Furthermore, Christians were given bigger representation in the Lebanese Parliament at the ratio of 11 Christian members versus 9 Muslim members. Those figures were subdivided to include sects, with the Maronites receiving the lion’s share.

The political Maronite establishment was eventually represented by a number of political parties; the most prominent of which is the Kata’eb Party (aka the Phalangists). This party trained and armed militia groups and played a major part in the Lebanese Civil War that devastated Lebanon in the 1970s and 80s.

The Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP), which has been mentioned in previous articles, remains thus far the only political party in the Levant that calls for the unity of Greater Syria. Soon after its establishment in 1932, it gained much popularity both within Lebanon and Syria. But this popularity started to dwindle after the highly charismatic Egyptian President Nasser rose to prominence advocating pan-Arab nationalism.

In 1952, Camille Chamoun was elected as president of Lebanon. He was a staunch supporter of an independent Lebanese identity. He became very unpopular amongst Muslim Nasserites and the Left. And after the declaration of union between Egypt and Syria in 1958 under the name of the United Arab Republic, Lebanese Nasser sympathisers saw an opportunity for Lebanon to join the union. In lieu of following the footsteps of their fathers by taking to the streets asking for Syrian unity, they demanded Arab unity instead.

In another twist of fate, looking at what is happening in the streets of Lebanon now, the grandchildren of the Lebanese Arab nationalists are now at the forefront, brandishing Lebanese flags, advocating Lebanese identity and demanding Lebanese sovereignty.

Back to the Chamoun era; civil unrest followed in 1958 and, finally President Chamoun asked the West to act on its promise to protect the integrity of Lebanon. The US Sixth Fleet was sent, Chamoun finished his term, and Army Chief Chehab was elected as president.

The tenure of Chamoun’s presidency however, marked the beginning of what is commonly termed as Lebanon’s “golden age”, the centre of beauty and vice which was discussed in a previous chapter. The Chehab period provided Lebanon with much needed stability to build on Chamoun’s era and Lebanon’s economy prospered.

When war broke out between Syria, Egypt and Jordan against Israel in June 1967, which later on became known as the Six-Day War, Lebanon was basically a spectator. All participating Arab states lost territory to Israel but Lebanon did not because it did not partake in the conflict. In the eyes of many Arabs, Lebanon was a Western implant, a pariah state, second worst only to Israel.

This was all to change, and so unpredictably. Lebanon was suddenly unable to remain isolated from its surroundings and the Arab/Israeli conflict reached its door step.

It all began when the PLO started to have a presence in Lebanon in the late 1960’s. As a result, in the closing days of 1968, Israel launched a brazen attack on Beirut airport and destroyed 13 airliner jets that belonged to the national carrier, Middle East Airlines, setting them alight. The international response was that of outrage. Lebanon was not meant to be part of the conflict and French President De Gaulle put a ban on French arms sales to Israel. This was the first military Israeli attack on Lebanon, but it was not going to be the last.

Only a year later, and after being pushed out of Jordan, the PLO moved into south Lebanon. This resulted in a number of skirmishes with the Lebanese Army but, later on in November 1969, Egyptian President Nasser brokered a deal between the PLO and the Lebanese Government which allowed the PLO to move its major base for its operations against Israel to Lebanon. Rachid Karami, the then Lebanese Prime Minister, refused to be the Lebanese official to sign the document. He did not want his endorsement to be seen as that of a Sunni leader compromising the sovereignty of Lebanon. Instead, the Army Chief, Emille Boustany (a Maronite), was asked to go to Egypt to ratify the agreement.

The agreement became known as the “Cairo Agreement” and it was successful in easing the tension between the Lebanese Army and the PLO, but it opened a Pandora’s Box to other tension and conflict.

Proponents of Lebanese identity, i.e., the Maronite political establishment, accused the PLO for creating a state within a state and blamed it for dragging Lebanon into confrontation with Israel; a matter that did not concern it. The Lebanese Left disagreed and argued that Lebanon could not bury its head in the sand and pretend that the Arab/Israeli conflict did not include Lebanon and that – with or without the presence of the PLO – Lebanon would eventually be dragged into taking its rightful place in history.

By the mid 1970s, the division in Lebanon over the issue was so intense that it was ripe for a civil war, and that was exactly what happened.

Four and a half decades later, Lebanon is still reeling from the outcome of that Civil War and all the identity issues that have been tugging it in different directions; one advocating for it to be in the bosom of the West, and the other to be at the forefront of resistance. In 1975 however, no one ever imagined that there would be a Lebanese force as mighty and organized as Hezbollah; a force that changed all formulations and predictions and redefined Lebanon.

This takes us back to the Lebanese Shia. Up until the mid to late 1960s, the literacy rate among Lebanese Shia was low, and they mostly lived in neglected villages in the Bekaa Valley or South. The living situation there was very dire, and many Shia moved to live in poorer outskirts of Beirut. Their situation there was not much better, but at least there were work and education opportunities.

Back when the Lebanese constitution was agreed to and written, the Shia were the underprivileged sector of the Lebanese community, the neglected ones, or the “Mahroumin” (the deprived ones) as the leader, Imam Moussa Assader, eventually named his movement. In a move that is akin to other Lebanese sects, Assader urged the Shia to take arms. He was renowned for saying “arms are the ornaments of men”.

The Mahroumin movement eventually morphed into Amal (meaning hope), and eventually, Hezbollah rose to existence as a splinter group after the Israeli invasion of 1982, all of which shortly followed the disappearance of Imam Moussa Assader in Libya in 1979.

Without going much into details, what is pertinent here is that when the Lebanese Civil War broke out in 1975, it was between the Right wing predominantly Christian militia on one hand, and the PLO and Lebanese Left on the other hand. And even though the Left had many members and leaders who were Shia, the Shia as a group were not a party to the conflict.

By the mid to late 1970s, friction started to develop between different PLO factions and the people of South Lebanon who are mainly Shia. I will deliberately avoid the argument of taking sides here not only because there are many sides to it, but also because the issue at hand is the actual conflict and not its causes. Either way, by the time the Israeli invasion of Lebanon took place in June 1982, many Lebanese houses flew white flags and greeted the Israelis almost like liberators. Some readers, especially those who have never been to Lebanon will disagree, but I have experienced and seen this with my own eyes. In no time at all however, the Israeli occupation revealed its true nature and the initial attitude towards it by those Lebanese dissolved within weeks and the resistance started to take form.

Surviving Palestinian civilians returning to the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila in Beirut after the massacre carried out by Phalange-linked militiamen, September 21, 1982. The massacre was organized by Israel after the Reagan administration gave it the “green light” to invade Lebanon earlier that year | Alain MINGAM/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Israeli Defence Minister Ariel Sharon riding in an IDF armoured personnel carrier to link up with Lebanese Falange Christian forces in East Beirut, Lebanon, June 15, 1982 | Bettmann/Getty Images

In the late 1980s, the Civil War was coming to an end, and as Lebanon was already decimated, the Maronites, Sunnis and Druze were all growing battle weary after fighting each other, the Shia began to take a more leading role. Justified by the Israeli occupation of South Lebanon, Hezbollah rose to prominence as a liberating force.

In hindsight therefore, as the Maronites, Sunnis and Druze were fighting over the division of power and how to split the spoils, they inadvertently not only weakened themselves, but also ended up empowering the forgotten group; the Shia.

Hezbollah proved to be a formidable force capable not only of engaging in guerrilla warfare with Israel, but also actual battle. For that reason, it gained unprecedented support and respect, not only within Lebanon, but also within the entire Arab World and beyond.

When the war on Syria took form, Hezbollah proved to have the power of a regional player, and not only that of a domestic one. Its involvement in Syria was instrumental in turning the tide in favour of the Syrian Government. All the while, as Syria and Hezbollah were scoring military victories within Syria, the Saudi/American influence in Lebanon was fading. The so-called 14th of March coalition was already fragmenting and losing momentum.

The once Western vassal has made a 180 degree turn and Lebanon catapulted itself right out of the Western sphere of influence. Not only it was no longer the Switzerland of the East, but it became the heart and centre of the anti-Israel Axis of Resistance.

As the Civil War in Lebanon was winding down in 1989, the warring parties met in Taif, Saudi Arabia, to reach an agreement. The agreement (known as the Taif Agreement) did not declare clear winners and losers, but stipulated that Muslims have equal number of members of Parliament to replace the former 11-9 ratio of the 1943 constitution. Later, the Lebanese Forces were disarmed, and their leader Samir Geagea was imprisoned.

Clearly, the traditional political Maronite establishment was seen as the undeclared loser of the war.

Michel Aoun

Almost in parallel to the rise of Hezbollah to prominence, former Lebanese Army Chief Michel Aoun attempted to gain popularity amongst Lebanese Christians by blaming his political rivals, i.e., the Phalangists and their off-shoot, “The Lebanese Forces”, for the dilution of the Christian power in Lebanon and the loss of the Civil War to the Left. According to his argument, the traditional Maronite political establishment has failed its obligation in protecting the position of the Lebanese Maronites, as stipulated by Patriarch Howayyek. He offered himself and his movement to replace the failed traditional Maronite political powers and to be the proper protector of the Maronites. This move split the Maronites and allowed him to challenge the traditional leaders and their political parties.

As a former enemy of Syria living in exile in France for 15 years, Aoun approached Hezbollah as a potential political ally and, Hezbollah in return, negotiated peace for him with the Syrian Government. All of this happened whilst Hezbollah was also entering the Lebanese political game and having elected members of parliament and eventually ministers.

The Lebanese political system is not a two-party system. The closest resemblance it has to a two-party system is that it is based on two coalitions of many minor parties. But those minor parties change sides quite often. It was therefore essential for both Aoun and Hezbollah to forge a strong alliance because, each of them alone, has control of no more than 15 per cent of the seats. They however, managed to rally up a majority, and eventually Aoun was elected as President in 2016.

Forward to the present moment, traditional Sunni, Maronite and Druze leaders are now all united in their anti-Hezbollah stance. In more ways than one, they seem as if they wish they could wind back the clock to the pre-Civil War days when their power-sharing excluded the Shia. The current street uprising however is presenting a new phase; as we shall see in the next chapter of this series.

V. A century-long “Mark Time”

A Lebanese woman waves Hezbollah’s flag in Dahiyeh, Beirut’s southern suburb, in February 2016 | Al-Akhbar\Haitham

“Mark Time” is a military march term that means marching in place without moving forward, and this is what Lebanon seems to be doing despite the many steps it took in lifting its position in the past and its mark in history recently.

The victories of both Hezbollah and Aoun came at an economic cost to Lebanon even though Lebanon was not placed under Western sanctions as such. The newly appointed Lebanese cabinet is not even able to approach friendly neighbours for financial assistance because it is tainted with corruption. Corruption however has been used as an excuse to sideline the Lebanese Government, but this is because of its close links with Hezbollah, and not because of corruption alone.

As the spearhead of the Axis of Resistance, Lebanon was not only trying to lick its wounds after a decade and a half of devastating civil war, but it was no longer a tourist and banking hub for visitors and investors alike. Furthermore, many Lebanese from different religions and sects did not want Lebanon to morph into such a status and preferred to see Lebanon returning to its former “glory” even if this meant kowtowing to the American/Israeli roadmap.

The power imbalance between the Israeli war machine and the Syrian army might have changed in favour of Syria as the war on Syria has managed to create a much more advanced Syrian Army. Prior to this development however, Syria did not have the advanced military hardware to engage in a conventional war with Israel directly, and Lebanon became the recipient of Syrian and Iranian military aid given to Hezbollah to resist Israel at an asymmetric, non-conventional level. This angered the anti-Syrian/Iranian sector of the Lebanese community even further.

By 2016, the American/Israeli/Saudi camp had lost its ground in Lebanon and Lebanon was, in theory, on the verge of capitalizing on a hard-earned victory that was achieved against all odds. The battle not yet won however, was the one against corruption, and this is shaping up to be the biggest challenge thus far.

The economy is in ruins and Gibran Bassil (Aoun’s son-in-law), has purportedly amassed $11 Bn in stolen monies from the Lebanese public and public purse, but he is not alone. Virtually all traditional Lebanese political leaders are now accused of major theft and it is believed that there is a total of $800 Bn in looted monies. The state debt is in excess of $15 Bn, the coffers of the central bank are almost empty, and the Government is unable to meet its debt repayment commitments. Adding insult to injury is the fact that there is a huge untapped gas deposit recently discovered off the coast and within national waters, but the government is too inept to capitalize on it to inject the economy with badly needed funds.

As the Lebanese anger spilt into the streets demanding all politicians to be held accountable, one would find it very surprising if the West did not see in the phenomenon a window of opportunity to jump onto the band wagon and find another foothold in Lebanon; one that is on the surface endorsed by the legitimate will of the people in their battle against very corrupt government officials and establishment.

Consumed by anger, a sense of being deceived and robbed clean, the Lebanese people felt more united than ever, and they have been able to express their unity under the banner of the Lebanese flag; the same flag that was repudiated and ridiculed two generations ago.

But does this mean that the majority of Lebanese people have had an “awakening” and finally realized that they are all Lebanese and that there is no further need to squabble over their identity? Does this mean that the majority of Lebanese have by now endorsed Patriarch Howayyek’s vision and that they fully uphold the Lebanese identity and political integrity and total independence from anything Syrian or Arab? On the surface, the easy answer that comes to mind is yes, but at a deeper level, this is not the case; and this is neither unrealistic nor pessimistic to say.

What is uniting the protestors at a political level is, in reality, their aversion to Syria, Hezbollah and Iran. Because Hezbollah is a political ally of Aoun and has senior ministers in the cabinet, the mainstream media rhetoric is hijacking the anger, making Hezbollah, Syria and Iran appear as if they are the cause of all mayhem and corruption.

One must be honest here and state that the corruption has taken place under the watchful eyes of Hezbollah and it either should have stopped it if it was able to, or stepped aside. It did neither. That said, the culprits behind public theft are the traditional Sunni, Maronite and Druze leaders; and this includes virtually all of the so-called 14th of March Coalition politicians, i.e., the Hariri camp. Shiite Amal leader, Nabih Berri, has also been named as a huge benefactor of corruption. Furthermore, not a single Hezbollah official has been named or caught with his hand in the cookie jar, but the street anger is focused against Hezbollah and its leadership. There are also accusations that Hezbollah has been sending thugs to hit and intimidate protestors and videos were produced to prove it, but in reality, none of these accusations can be adequately corroborated.

Is Hezbollah at fault in all of this? As I have indicated in some Saker articles, I believe that Hezbollah’s biggest mistake was to enter Lebanese politics. Lebanese politics is a piece of dirt, and dealing with it soils one’s hands, irrespective how careful one is. But even if the resistance wing of Hezbollah decides to quit politics now, and leave the people’s representation in the hands of allied politicians, it cannot wind back the clock.

It must be emphasized repeatedly that the Lebanese uprising is legitimate in as far as its demands for reform and holding politicians accountable for their theft. Apart from the agitators and implants sent to wreak havoc, those who took to the streets plus those who stayed at home and supported them in their hearts and minds are all united. But they are united by this common interest only.

At a deeper philosophical level however, the divisions within the Lebanese people are still there; only the players and their aspirations have changed. If we go back to 1920, the main proponent of Lebanese identity and independence was only the section of the Maronites who were supportive of Howayyek’s model. The Lebanese Left did not exist back then, but patriotic Lebanese from Maronites, other Christians, as well as Muslims were all against it. They wanted to be reunited with Syria. Nearly half a century later in 1975, on the eve of the Civil War, the identity rift was between the Right wing Maronite militia on one hand, and the PLO and the Lebanese Left on the other hand. The former regarded Lebanon as a part of the West and the latter regarded Lebanon as a part of the Arab World and that it had an obligation towards Palestinians.

Apart from standing up against corruption and the utter failure of the state and its political custodians, today’s uprising continues to be about the definition of Lebanon and its regional place. The divisions today are between the Axis of Resistance and the proponents of the West. The players have changed slightly, but they are still playing the same game that divided their parents, grandparents and great-grandparents before them.

Those now flying Lebanese flags continue to have the traditional Right wing Maronite establishment at their core, but this time they include some who have almost overnight become vehemently Lebanese. They are mainly the section of the Sunnis who are anti-Hezbollah and anti-Syria sympathizers. But the Christian voice itself has now been split between that of the traditional Maronite establishment and the supporters of Frangieh and Aoun. Frangieh, a Maronite leader, the grandson of Lebanon’s President Suleiman Frangieh at the time the Civil War commenced, is vehemently pro-Syria, pro-Hezbollah and against the Right wing “Lebanese Forces”. And though he is a political rival of President Aoun, the two are united on the same political platforms.

And if one dissects the passion of Sunnis who are anti-Syrian, anti-Hezbollah and anti-Iran, one can clearly see the sectarian undertone of aversion towards anything that is perceived as Shiite.

On the other side of the divide, the Axis of Resistance has Hezbollah at its centre (which is Shiite), supported as per above by two Christian leaders; Aoun and Frangieh, and by what is left of the Lebanese Left which includes Lebanese of all religions and sects.

It would be therefore inconclusive to say that a century after its inception, the people of Greater Lebanon have come of age and are united in endorsing the identity that Patriarch Howayyek and French General Gouraud had stipulated for them. If anything, the divisions now run deeper.

How will the uprising in Lebanon pan out is anyone’s guess, what is obvious however is that as Lebanon is poised to enter its second century, and as it turned from a pro-Western puppet state into the centre of the Axis of Resistance, the West is making another bid to pull it back under its belt by supporting the uprising allegedly in the name of human rights and giving the people what they want. If Lebanon goes the full circle, it will be to the detriment of the Axis of Resistance, but on the other hand for the hand of the West to be kept at bay, Lebanon will not be able to survive unless major reform is implemented and the economy is back on track.

Sadly, few among those squabbling are truly addressing the real identity question of Lebanon. They are looking everywhere in search of their identity and raison d’etre but ignoring the truth.

These articles are not intended to vouch for the SSNP and its argument that promotes the unification of Greater Syria, but with or without the SSNP, Lebanon is part of Syria and this is a historical and demographic fact.

In my personal view, the problems of Lebanon will not be resolved until Lebanese people come to the realization that they are not superior to Syrians as many of them think, but that they are the same people. The presence of the Syrian Army in Lebanon between 1976 and 2005 provided an excellent opportunity to bring the hearts and minds of Lebanese and Syrians back together. In hindsight, it was a wasted opportunity that ended up deepening the fissure instead of healing it.

Either way, Lebanon had had its run as an independent nation state and it failed. Until someone comes with a magic potion, its infrastructure has been relegated, it remains heavily in debt and polluted, and its people remain divided in their loyalties.

THE END

Slightly edited for spelling and grammar by TS, with the addition of maps and photos (not all!).

Ghassan and Intibah Kadi are analysts of Middle East affairs and contributors to this blog. Ghassan Kadi, a native of Beirut, is the author of An Epic of Integrity: The Chronicles of the War on Syria (June 2016). Visit Intibah and Ghassan Kadi’s website.